Brief History of Hatchery Presence and Removal

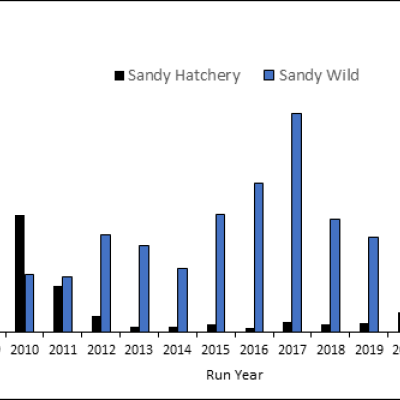

The Salmon River Hatchery was built in 1975 and first released yearling Coho Salmon into the river in 1978. In 2005, it was determined by ODFW biologists that the hatchery was the principal threat to wild salmon and the Coho hatchery program ended in 2008, though Chinook are still produced at the Salmon River Hatchery. Within a few years of the Coho hatchery program ending, the number of natural spawners in the Salmon River were equal to or even greater than the number of hatchery Coho salmon that had been returning for the previous ~30 years. This was true even when conditions were generally unfavorable for salmon between 2009-2016.

At the same time the hatchery was installed, major restoration of the Salmon River estuary began. It is likely that the combination of ending the hatchery program and the restoration of the estuary environment has led to the remarkable recovery of wild Coho in the Salmon River.

Recent research indicates that there has been a substantial increase in Coho productivity and abundance of wild Coho since the end of Salmon River Coho hatchery program. In addition, rivers where hatchery Coho stocking had previously ended already had higher abundances and productivity in the same years where there were low returns of both hatchery and wild Coho in the Salmon River (Jones et al. 2018).

Size of Wild Population Pre-Hatchery

1975-76 estimate: 1,500, after ocean harvest of 70-85% (pre-harvest = 5,000-10,000)

Data from 2011 ODFW presentation slide deck

Size of Wild Population During Hatchery

1995-2008: mean = 323 (range = 15-1,801)

2009-2011: mean = 2067 (range = 810-3,868), transition period when some hatchery-raised fish were a portion of the spawners

Size of Wild Population Post-Hatchery

2012-2016: mean = 1603 (range = 362-4,279)

All data other than pre-hatchery estimate from Jones et al. 2018.

Supporting Materials

NFS Salmon River Watershed Page

Restoring the River Salmon: The Coho Return

Recovery of Wild Coho Salmon in Salmon River (Oregon)

Jones, K. K., Cornwell, T. J., Bottom, D. L., Stein, S., & Anlauf‐Dunn, K. J. (2018). Population viability improves following termination of Coho Salmon hatchery releases. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 38(1), 39-55.

Nickelson, T. (2003). The influence of hatchery coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) on the productivity of wild coho salmon populations in Oregon coastal basins. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 60(9), 1050-1056.

Theriault, V., Moyer, G. R., Jackson, L. S., Blouin, M. S., & Banks, M. A. (2011). Reduced reproductive success of hatchery coho salmon in the wild: insights into most likely mechanisms. Molecular Ecology, 20(9), 1860-1869.