Deschutes Diaries: Hatcheries In The Deschutes Basin - A History (Part 1)

Deschutes Diaries

Hatcheries In The Deschutes Basin - A History (Part 1)

December 2025

Welcome back to the Deschutes Diaries! In this series, we delve into the dynamics of the Deschutes River, examining its past, present, and future challenges. In this issue, we explore the the history of hatcheries in the Deschutes Basin.

Through these articles, we’ll take a closer look at the events that shaped the Deschutes River we know today, and highlight Native Fish Society's efforts to protect and revive its wild abundance.

This is an ongoing series to showcase and open the conversation of our Deschutes: Return to Wild & Cool campaign. Along the way, we’ll be sharing important milestones, ongoing efforts, and how you can be a part of this vital work. Additional parts and updates will be posted over the next several months. Stay tuned!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In recent conversations with members, it’s been repeated how crucial it is to know not only what Native Fish Society (NFS) is against, and why, but what we’re for.”

On the Deschutes River, NFS proudly advocates on behalf of all three legs of the stool for achieving wild abundance: Wild Fish, Healthy Rivers, and Sustainable Fisheries.

To know where we’re going, it’s important to ask two important questions: First, “Where are we?” Followed by, “How did we get here?”

So, in this Part I of our Hatcheries in the Deschutes series, we hope to answer those questions by bringing you up-to-speed with artificial fish production in the Deschutes Basin, and laying out the current state-of-affairs.

Why is this important?

Wizard Falls Hatchery

History

Wizard Falls Hatchery was constructed in 1947. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) stocked the Metolius River with hatchery fish raised at Wizard Falls Hatchery. Over time, research has found that stocking hatchery fish has a detrimental effect on wild fish, including competing with them for space and food, and less-fit offspring upon interbreeding. Studies in the 1990s found that wild Metolius River redband trout were hybridizing with hatchery rainbow trout, which also made them more susceptible to diseases. The state ended the stocking program in 1996, allowing the native, wild redbands to reclaim the Metolius River as their own once again.

“The Metolius River was one of the first trout rivers to be managed as a wild, native fishery in the state of Oregon. Stocking of hatchery rainbows began in the Metolius in 1938. Over twenty-five years ago, wild fish advocates campaigned to rewild the Metolius, and despite stiff local opposition, stocking of rainbow trout ceased in 1996. Today, redd counts have increased fifteenfold since counts began, and the trend is continuing to move upwards. The Metolius is one of the best examples in the West that demonstrates wherever healthy habitat and cold water persists, Mother Nature can and should be left alone to work her magic. The Metolius's native fish are an incredible, abundant natural resource there for all of us to appreciate,” Metolius River Steward Adam Bronestein wrote for NFS.

Current Program & Goals:

Hatchery Program Management Plan ( HPMP), 2024)

Wizard Falls Hatchery’s resident fish programs are harvest programs meant to boost recreational fishing opportunities. They include incubating and rearing kokanee, tiger, brook, and rainbow trout, as well as holding brook trout for air-stocking. The Deschutes River stock summer Steelhead programs are conservation programs**, and the incubation and rearing of summer steelhead are part of a reintroduction program in the upper Deschutes Basin. Approx 152,000 eyed eggs from Deschutes River broodstock adults are taken from Round Butte Hatchery to rear 100,000 smolts for release into Wychus Creek and Crooked River.

-

**ODFW defines Conservation hatchery programs as operations “to maintain or increase the number of naturally produced native fish without reducing the productivity (e.g., survival) of naturally produced fish populations. Conservation hatchery programs shall integrate hatchery and natural production systems to provide a survival advantage with minimal impact on genetic, behavioral, and ecological characteristics of targeted populations. Implementation shall proceed with caution and include monitoring and evaluation to gauge success in meeting goals and control risks.

Long-term conservation success shall be tied to remediating the causes of the decline that resulted in the need for hatchery intervention. Once goals are met, then the hatchery program will be discontinued.

The hatchery program management plan may be designated as one of the following conservation hatchery program types:

(a) Supplementation, which routes a portion of an imperiled wild population through a hatchery for part of its life cycle to gain a temporary survival boost, or brings in suitable hatchery produced fish or naturally produced native fish from outside the target river basin to supplement the imperiled local population;

(b) restoration, which outplants suitable non-local hatchery produced or naturally produced native fish to establish a population in habitat currently vacant for that native species using the best available broodstock;

(c) captive brood, which takes a portion or all of an imperiled wild population into a protective hatchery environment for the entire life cycle to maximize survival and the number of progeny produced;

(d) captive rearing, which takes a portion of an imperiled wild population into a protective hatchery environment for only that part of its life cycle that cannot be sustained in the wild;

(e) egg banking, which temporarily removes a naturally produced native fish population from habitats that cannot sustain it and relocates the population to another natural or artificial area that can support the population;

(f) cryopreservation, which freezes sperm from naturally produced native fish for later use in conservation hatchery programs;

(g) experimental, which investigates and resolves uncertainties relating to the responsible use of hatcheries as a management tool for fish conservation and use.”

Fall River Hatchery

History

The original portion of the Fall River Hatchery construction was completed in 1929.

Current Programs & Goals

Fall River Hatchery programs are harvest programs, used for the augmentation of fishing and harvest opportunities, which includes releases into the Fall River, Deschutes District waterbodies, and what the HPMP calls “various water bodies.” The Deschutes River spring Chinook programs are conservation** programs for the reintroduction of spring Chinook into the upper Deschutes basin.

Oak Springs Hatchery

History

Oak Springs Hatchery was constructed in several phases beginning in 1922, with the last major construction in 1996.

Current Programs & Goals

The facility is currently used for egg production, incubation, and rearing of two stocks of Rainbow Trout, incubation and rearing of summer Steelhead and winter Steelhead, and maintains two resident Rainbow Trout broodstock. The goals of the summer steelhead programs are listed as, for Deschutes River Stock Produce, “catchables to meet statewide trout management program objectives,” and for Clackamas River stock, to “help meet PGE and City of Portland mitigation agreement goals, and to provide sport harvest opportunities on hatchery winter steelhead in the lower Clackamas River without intentional risks to naturally producing populations.”

Round Butte Hatchery

History

Round Butte Hatchery was constructed in 1972 to mitigate the fishery losses caused by the Pelton/Round Butte (PRB) Hydroelectric Complex. Pelton Ladder, a former fish passage ladder, is operated as a satellite rearing facility, with some sections converted for rearing fish.

Current Programs & Goals

Round Butte and its satellite (Pelton Ladder) are used for adult collection, egg incubation, and rearing of spring chinook and summer steelhead. Round Butte Hatchery has both harvest and conservation** programs. The Deschutes River Spring Chinook and Summer Steelhead Programs are harvest programs that provide fishing and harvest opportunities in mitigation for habitat loss and migration blockage resulting from the construction of the Pelton Round Butte hydroelectric project. The Hood River Spring Chinook program is a conservation** program used for the restoration of a wild fish population in currently vacant habitat.

The Pelton Round Butte Hatchery operates under the following goals:

Hood River Spring Chinook

Release up to 250,000 yearling spring Chinook salmon smolts annually into the Hood River Basin to re-establish and maintain a naturally sustaining spring Chinook salmon population sub-basin and provide sustainable and consistent tribal and sport harvest opportunities.

Deschutes River Spring Chinook

Produce 380,000 spring Chinook smolts to mitigate for losses caused by Pelton Round Butte.

Raise 100,000 spring Chinook juveniles for transfer to the Hood River acclimation site.

Utilize hatchery broodstock to provide 128,000 eyed eggs for Fall River Hatchery to produce 100,000 spring Chinook smolts annually. These smolts will then be acclimated and released above the Pelton Round Butte Project in an attempt to restore self-sustaining and harvestable populations of native Chinook in the Deschutes and its tributaries, and to “reconnect native resident fish populations that are currently fragmented by Pelton Round Butte.

Deschutes River Summer Steelhead

Produce 162,000 smolts annually to mitigate for production and habitat losses caused by the Pelton Round Butte Project.

Produce 30,000 post-smolt steelhead yearlings for release into Lake Simtustus as catchable trout to mitigate for production and habitat losses caused by Pelton Round Butte.

Produce 3,000 post-smolt steelhead yearlings for release into Jefferson County Fishing Pond as catchable trout.

Utilize hatchery broodstock to provide 128,000 eyed eggs for Fall River Hatchery to produce 100,000 summer steelhead smolts annually. These smolts will then be acclimated and released above the Pelton Round Butte Project in an attempt to restore self-sustaining and harvestable populations of native Chinook in the Deschutes and its tributaries, and to “reconnect native resident fish populations that are currently fragmented by Pelton Round Butte.

Produce 10,000 post-smolt steelhead yearlings for release into Haystack Reservoir as catchable trout.

Warm Springs National Fish Hatchery (WSNFH)

History

WSNFH was a vision of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon (CTWSRO) since 1959, when the Service was asked to investigate the possibilities of salmon and steelhead enhancement on the reservation. The hatchery enhances Tribal fisheries on the Reservation and traditional fishing areas and natural-origin fish populations in the Warm Springs River.

Congress authorized the construction of the Warm Springs Hatchery in 1966. Fish production began in 1978 with eggs from wild spring Chinook Salmon and steelhead (O. mykiss) captured from the existing natural runs passing the hatchery site. The steelhead program was terminated in 1981 because of disease, growth problems, and physical limitations of the facility. To protect wild steelhead, only wild steelhead are passed above WSNFH.

Current Programs & Goals

Operations at the hatchery presently consist of adult collection, egg incubation, and rearing of spring Chinook salmon. The current hatchery broodstock objective is to spawn 650 - 693 Chinook Salmon adults. 726 - 770 adults are collected for broodstock proportionately through the run based on wild stock timing and may be adjusted if temperatures exceed 16 °C.

To maintain the stock integrity and genetic diversity of hatchery and wild spring Chinook salmon, approximately 10 percent natural origin fish have been incorporated into broodstock collection based on pre-season forecasts and in-season run size updates. However, if the wild run is less than 1,000 fish, no wild fish will be collected for broodstock.

In a USFWS review of the WSNFH spring Chinook salmon program, the Hatchery Review Team recommended that the program maintain the current goal of a minimum of 10 percent natural origin spring Chinook Salmon in the broodstock and continue to limit hatchery-origin spring Chinook salmon on the spawning grounds to less than 10 percent.

During years of low returns to the hatchery or unexpected losses to production, consideration has been given to augmenting the hatchery production with eggs or juveniles from other hatchery programs. The primary source of eggs during years of shortfall is from ODFW’s Round Butte Hatchery (RB), located within the Deschutes River Basin. Eggs and juveniles from Parkdale Hatchery, located within the Hood River Basin, have also been used to augment the WSNFH production in recent years.

To maintain the WSNFH genetic stock, any releases from non-WSNFH stocks are differentially marked (e.g., left or right ventral clip) and coded-wire tagged to distinguish them from WSNFH fish upon return. These stocks are excluded from the broodstock and distributed to the CTWSRO or to RB if needed. If returns to WSNFH are projected to be below broodstock needs, RB fish returning to WSNFH may be spawned and their progeny reared and marked separately from WSNFH stock. When considering whether to rear and release non-WSNFH stock fish, managers must consider the risks and benefits of such actions.

Present Day:

With almost 100 years of history of hatcheries in the basin, it’s about time we take stock of the return on this investment and define success.

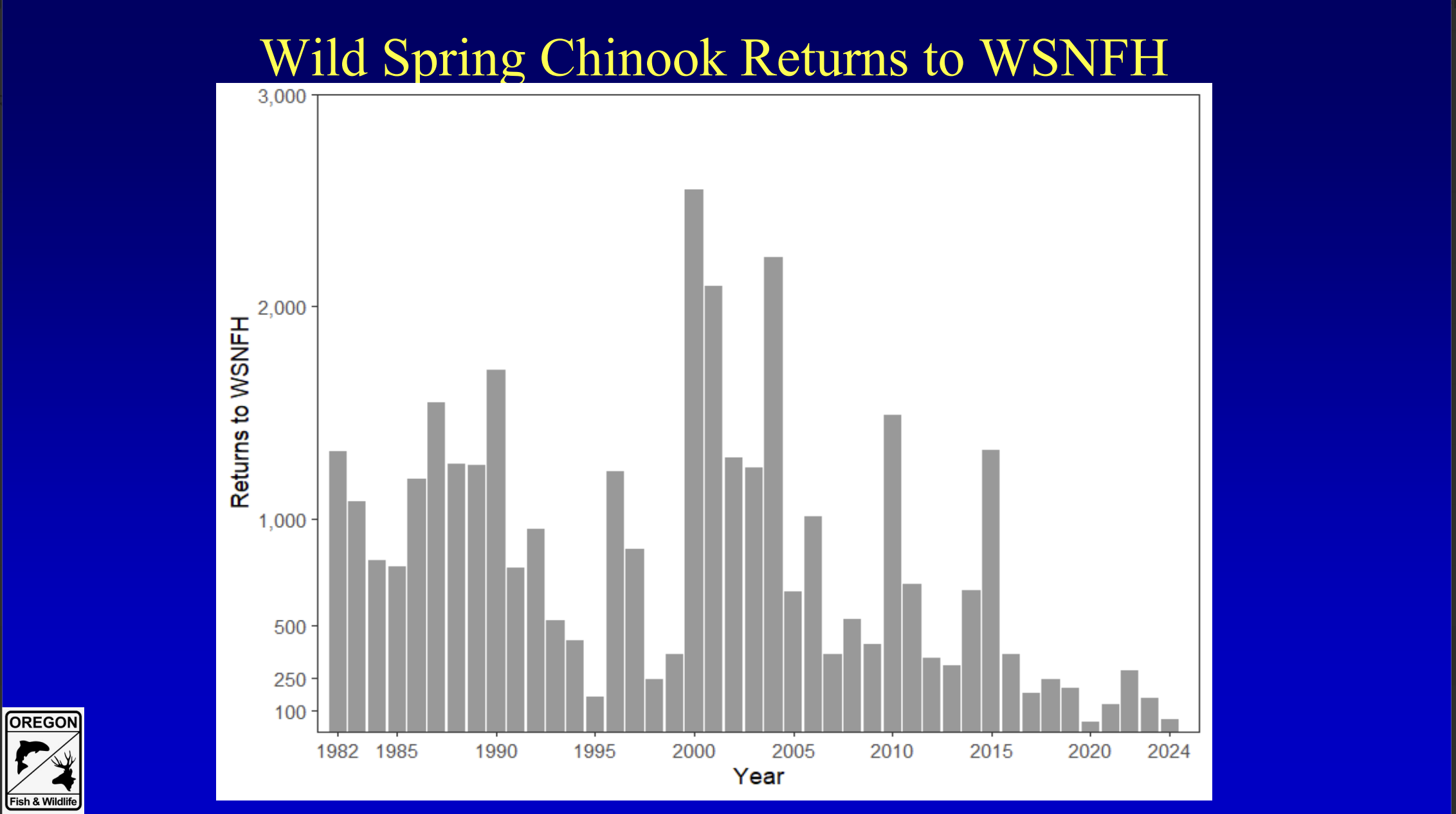

Anadromous returns of wild salmon (55 wild spring Chinook returning to the Warm Springs River in 2023) and wild summer steelhead (so variable that fishing seasons are managed on a Framework based largely on mainstem Columbia wild fish passage) are on year-to-year life support.

At the same time, we’re experiencing continued - and documented - stability of the all-wild Redband trout populations of the lower Deschutes River, and the robust escapement of more than 40,000 wild fall chinook registered by ODFW in 2024.

Important to remember: The Deschutes River boasts one of the healthiest runs of wild fall Chinook salmon remaining in the Columbia River basin. No hatchery program exists for fall Chinook on the Deschutes.

Not to mention, we have clear evidence of wild fish succeeding in healthy rivers that are allowing sustainable fisheries (See Oregon Coastal Coho Recipe For Success).

As self-sustaining adult returns of salmon and steelhead to the Deschutes River reintroduction effort above the Pelton Round Butte Complex continue to underwhelm - to say it kindly - the question begs to be asked: What is the best path forward?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Other Relevant Sources:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Deschutes Diaries is an ongoing series. Stay tuned for upcoming topics!

Next month, we'll cover Deschutes' wild fish and their history, followed by Part II of Hatcheries in the Deschutes Basin, where we’ll take a closer look at NFS’s concerns for how these hatchery programs affect wild fish populations in the Deschutes, and what can be done about it, now, and in the future.

If you have any questions or topics you'd love to see covered in Deschutes Diaries, please don’t hesitate to reach out – we’d love to hear from you! Send us an email with your questions and suggestions at info@nativefishsociety.org

Want to stay updated on Deschutes topics? Sign up here: